HADACOL!

by Brent Coleman

HADACOL!

by Brent Coleman

Fifty years ago and for approximately two years, before the bubbe burst, residents of the then mostly dry Tombigbee Country could get a boost in their spirits at their neighborhood grocery store. A new, exciting patent medicine exploded on the scene, and if it never, as advertised, cured all ills, it sure did make area residents who bought it feel better.

In 1949 and 1950, no one coud read a newspaper or listen to a radio without reading or hearing of the miracle cures brought on by a new patent medicine- HADACOL. The radio commercials and testimonial ads for the miracle medicine from Louisiana were so ridiculous, they were amusing, as Mr. or Mrs. or Miss So-and-so proclaimed that he or she had taken HADACOL and been cured of cancer, epilepsy, heart trouble, strokes, tuberculosis or whatever ailment the buyer might have or imagine he had.

Personally I saw the results of one of the product's success stories. I had a cousin who had never had a date in her life, could not ride in a car without becoming violently ill and was resigned to be the old maid daughter who stays at home the rest of her life to tend the aging parents. Then she began taking Hadacol and felt so much better, she got a new lease on life, ventured out and married. HooRay for HADACOL! Another miracle cure!

Even doctors will tell you that many illnesses are psychological and many will admit that alcohol when taken in moderation can, in some cases, be very beneficial. In no time at all, however, the FTC (FEderal Trade Commission) stepped in and made the company stop making claims to be a cure-all, but even without the claims Hadacol had caught on and sales skyrocketed thorughout the South.

A song, "Hadacol Boogie," rose to the No. 1 spot on the Hit Parade and the entire South was dancing to it, and being bombarded with commercials about it, drinking countless millions of bottles of it and laughing at it. The man behind all the hysteria ws laughing, too, all the way to the bank. HADACOL was the brainchild of Senator Dudley J. LeBlanc of Lafayette, Louisiana.

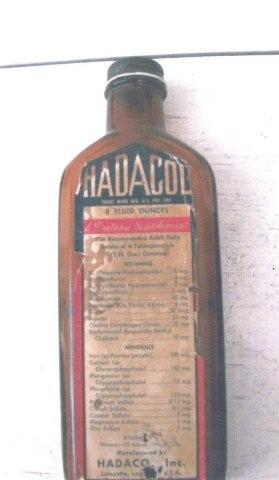

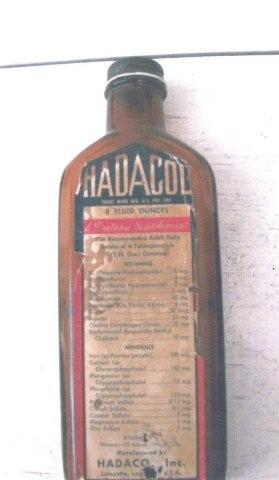

Like Coca-Cola, another product that no one coud ignore ads for, the ingredients of HADACOL were a carefully guarded secret. However, Sen. LeBlanc once told a confidant the medicine contained enough alcohol to make people feel good and enough laxative for a movement.

From the beginning of the nation, men had made a living sellig patent medicine, which in many cases they claimed cured all ills. With the advent of radio these "snake-oil" salesmen found it to be a bonanza for selling their products. Many of these men developed the skill of selling to an art, but one man developed the art to the point that he made all other "snake-oil" salesmen look like rank amateurs. He was the Cajun erstwhile politician, Dudley Joseph LeBlanc.

LeBlanc was born in Youngsville, Louisiana, on August 16, 1894, and claimed to be able to trace his ancestry back to Rene' LeBlanc in Longfellow's Evangeline. He grew up speaking nothing but French, and never lost his heavy Cajun accent.

After graduating from Southwestern Louisiana Institute, he became a salesman for a shoe company, working the same area of northern Louisiana as Huey P. Long. LeBlanc and Long both were formidable salesmen, and they came to mistrust, then detest each other as only salesmen can.

After World War I, LeBlanc got his introduction to selling patent medicines when he started reprsenting Cardui, a "woman's tonic." His first brush with politics came in 1924, when he ran for the state legislature in Vermillion Parish and won. In 1932 he ran for governor, but Huey Long, who had also turned from selling to politics, saw that he was defeated.

LeBlanc then decided to market his own patent medicine, reasoning if he was so good at selling someone else's he could profit more from selling his own. But first he had to have a medicine.

He started with Happy Day Headache Powder, a concoction that, like his other products contained a stiff dose of laxative. It had a so-so success but he still could not get politics out of his system.

He made another try for the governship in 1942 and after once again being defeated, he fell ill of beriberi. He was cured with vitamin B-1 compounds and as a result began a serious study of vitamins and their cures. He then began distilling his own compound in the family barn. It was a mixture of vitamins, minerals, honey, assorted other ingredients and - not the least - 12 percent alcohol. He dubbed his product HADACOL, an acronym from HAppy DAy COmpany, topped of with an L for LeBlanc.

His product had approximately the same alcohol content as wine, but at $3.50 a bottle was four times as expensive and immeasurably more foul-tasting. He explained that by saying unless the product tasted bad, the patients wouldn't feel it was doing them any good.

LeBlanc first tested his compound on the cattle in his barn, then himself and then his neighbors, and since, if none were remarkably cured, at least no one died from taking it, so he put it on the market in 1945.

Sales were static for a while as he rekindled his political ambitions, becoming a state senator in 1948. During his time in office he was instrumental in helping pass an old age prnsion bill, then used his newfound credibility among older citizens of Louisiana to sell Hadacol.

He realized that he needed to publicize his product if it were to sell, so he turned to newspapers and his newspaper ads were rife with testimonials from cured customers, and also included the fact that the good senator "has served his people in public life faithfully and well. In private life, he brings you a service which is appreciated by suffering humanity - HADACOL"

As he more and more realized the value of advertising on sales, he bgan saturation advertising and more or less was the first in the South to use that method of assuring sales.

Then early in 1949, LeBlanc hooked up with Murray Nash, then head of Mercury Records' Southern Division. Nash, realizing he might be on to a good thing, cut two songs about the product - one for the country market, Bill Nettles' "Hadacol Boogie," and one for the rhythm and blues market, Professor Longhair's "Hadacol Bounce."

The roaring success and good publicity generated by "Hadacol Boogie," convinced LeBlanc country music was the best for promotng his product. In October of 1949, he began sponsoring the Hank Williams Show on WSM.

Mass advertising had LeBlanc and in 1950 he spent more than one million dolars a month on advertising HADACOL, making him second to Coca-Cola in ad money spent in the nation. His enterprise grew to the point where Hadacol was shipped by his own fleet of wholly-owned trucks from his plants in Lafayette.

He had his thousands of employees dress all in white, to simulate a laboratory, a far cry from the barn in the same town where he had fed Hadacol to his cows. Researcher Floyd Martin Clay described how LeBlanc skillfully promoted Hadacol in areas where he hadn't secure distribution. He bought heavy advertising on radio in the form of a contest: a well-known song was played and the audience was invited to send in a card with the title. If they were correct, they got a voucher for a free bottle of Hadacol. Of course, Hadacol was nowhere to be found, but druggists were by then getting a steady stream of requets for it and pestering the jobbers to carry it. In time Hadacol trucks were waiting, ready to move in and jobbers were begging to sell it. At the peak of his operation in 1950 and '51, sales were as high as one million, five hundred thousand dollars a day.

Not ever content with the enormous number of bottles of his alcohol-laden tonic being sold, LeBlanc hit upon the idea of a caravan, a show that would attract people and thus more customers.

Then, according to LeBlanc,the idea hit him at 4:30 one morning, he would organize a Hadacol Caravan to perform shows and promote sales across the South. Perhaps he got the idea from the old Western snake-oil salesmen who used to move into a town, put on a short show to attract people, then sell their patent medicines, and the larger and later medicine shows at carnivals.

LeBlanc was fond of saying that the four S's of salesmanship were Saturation, Sincerity, Simplicity and Showmanship and with that in mind, he mounted the Hadacol Caravan. The first carvan ran in August 1950 and starred Roy Acuff, Connie Boswell, Burns and Allen, Chico Marx and Mickey Rooney. Admission to the show was restricted to those carrying Hadacol box tops.

The 1951 Caravan was the largest show of its kind ever staged: it was the last and greastest medicine show.

The mainstay of the bill was Hank Williams, backed by Minnie Pearl, comedian Candy Candido, emcee Emil Perra, juggler Lee Marks, a house band led by Tony Martin, and a troupe of dancers and twelve clowns.

Other stars who appeared in caravans included Caesar Romero, Jack Benny and Rochester, Milton Berle, Bob Hope, Jimmy Durante, Rudy Vallee, Carmen Miranda, Dick Haymes and Jack Dempsey. Admission was one Hadacol box top for children, two for adults. There were prizes for the kids and most shows were preceded by a parade.

However, LeBlanc realized that demand by then had peaked and he knew that the Food and Drug Administration, the American Medical Association, and the Liquor Control Board were all sniffing around. He also alone knew that the corporation was now spending more on advertising than it was making; the corporation had lost two million dollars during the second quarter of 1951 alone.

The last performance of the celebrated Hadacol Carvan was Friday, Sept. 14, in Wichita, Kansas. The show was scheduled to go on the following Monday, but over the weekend LeBlanc had finalizied a deal with the Toby Maltz Co. in New York to sell Hadacol. He announced the sale in Dallas on Monday, Sept 17, just before the show scheduled for the Cotton Bowl. The next morning at breakfast Hank Williams asked LeBlanc, "What did you sell Hadacol for?" (Southern for why did you sell it?). Leblanc answered, "Eight and a half million dolalrs."

In fact, LeBlanc never recieved more than $250,000 for Hadacol. Payments from Maltz called for half a million dolalrs a month, but there were no profits to meet that obligation to LeBlanc - liens, overdue bills, returned shipments and FTC and Liquor Control Board suits took what money there remained. LeBlanc had cleverly sidestepped disaster and he excused himself from responsibility by saying, "If you sell a cow and the cow dies, you can't do anything to a man for that."

LeBlanc once agian announced his candidacy for governor of Louisiana, but during the height of the campiagn, Hadacol was officially declared bankrupt. leBlanc caught the fallout and was tagged as a loser. He once again lost his bid to become governor in 1952.

-- article based on information from "The Biography of Hank Wiliams" by Colin Escott, 1994, and from personal experience, memories, and local research.